Inclusion

PERSPECTIVE

Just because organizations spend a lot of money and effort on diversity and inclusion objectives does not mean they will be successful—especially if their initiatives do no more than mitigate legal risk or focus on reducing exclusion. Inequity is common because most initiatives do not go far enough. For example, they still mistakenly define inclusion as the opposite of exclusion. Or they are often aware of one-dimensional employee demographics, but seldom look at complex minority combinations. Or they do not yet build inclusion practices into employees’ everyday experiences. Fortunately, the path to a more inclusive, more equal, and more successful culture is now more clear than ever.

“Companies that embrace diversity and inclusion in all aspects of their business statistically outperform their peers.”

—JOSH BERSIN, PRINCIPAL AND FOUNDER, BERSIN BY DELOITTE

in·clu·sion

n. the act of including, the state of being included1

INTRODUCTION

For many years, in multiple countries, dozens of rigorous studies have demonstrated the same conclusion: organizations with diverse and inclusive cultures deliver dramatically better results. Companies, corporations, government agencies, and other enterprises that possess inclusive cultures are twice as likely to meet or exceed financial targets, 6x more likely to be innovative and agile, and 8x more likely to achieve better business outcomes.2 Over three-fourths (78%) of organizations recognize these advantages and prioritize diversity to improve their cultures. However, most diversity and inclusion (D&I) initiatives fail to deliver on objectives and are often seen by both employees and leaders as hollow and ineffective.

Some of this may be due to the origins of D&I programs as risk-mitigation exercises for legal compliance that have led to enduring resentment among senior leaders. Strategies and technologies for D&I also tend to defeat themselves by segmenting people into categories, rather than celebrating the differences in individuals.

True inclusion runs much deeper than the variety of an organization’s employee demographics. It’s better reflected in the employee experience itself—the everyday interactions with coworkers, leaders, policies, and practices. To achieve an inclusive culture, leaders must first reframe how they think about inclusion. For example, many companies will spend significant time, money, and effort to hire for greater diversity. But if they don’t provide the opportunities for diverse employees to thrive, that hard-won talent will soon leave.

Johnny C. Taylor, Jr., President and CEO of SHRM, says,

“We often forget the ‘I’ in the D&I conversation. The challenge is in having a culture where all employees feel included. It’s a major investment to bring talent into your organization, so why bring them in if they’re not happy when they get here? You’ve got to get the inclusion part right.”3

Addressing D&I, especially now, when society is demanding racial equality and respect, requires us to reconsider what inclusion means within our organizational cultures. Real inclusion is a synthesis, a coming together, of unique individuals with their own combination of experiences, skills, perspectives, and personalities to enhance culture and business performance. Hiring diverse employees and then telling them to homogenize if they want to succeed is not a viable inclusion strategy. To be effective and sustainable, inclusion must start before the recruiting process, extend beyond onboarding, and permeate the entire employee experience.

“Inclusion and fairness in the workplace is not simply the right thing to do; it’s the smart thing to do.”

—ALEXIS HERMAN, FORMER UNITED STATES SECRETARY OF LABOR

FOR MOST ORGANIZATIONS, D&I INITIATIVES HAVE NOT WORKED

While organizations have implemented various strategies for promoting diversity and inclusion, few have made positive headlines. Only 44% of employees say their organization’s D&I efforts are sincere, while even fewer (34%) feel they are effective or believe inclusion is part of their culture.

Our research also shows minority employees face microaggressions at work far more frequently than other employees. (Microaggressions are generally small, commonplace indignities, intentional or unintentional. They may take the form of jokes, negative comments, backhanded compliments, derogatory questions, or any other minor insult, verbal and non-verbal.)

For example, we found employees with disabilities are much more likely to experience microaggressions from peers, leaders, and senior leaders than their colleagues without disabilities.

They’re also 54% less likely to feel they belong at an organization and 115% more likely to suffer from severe burnout.

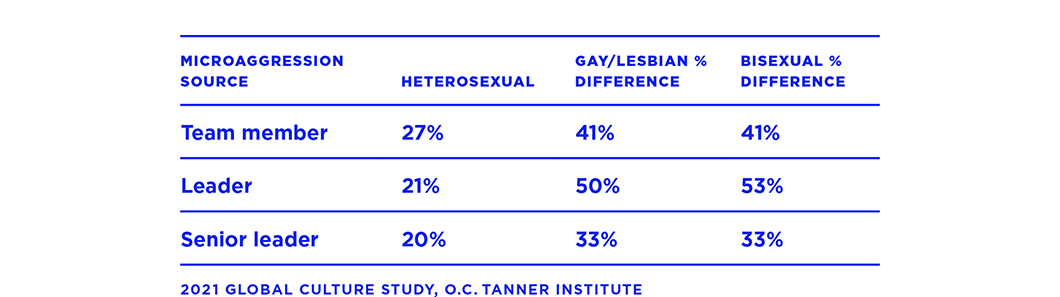

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual employees report similar experiences with microaggressions.

They’re also 63% less likely to feel they belong at an organization and 98% more likely to suffer from severe burnout.

Additionally, the Center for Talent Innovation found 59% of Latino men and women in the US experience microaggressions in the workplace, 63% do not feel welcome at work, and 46% of Black women feel their ideas are not heard or recognized.4 Simply put, microaggressions are an extremely large obstacle to inclusion, regardless of organizational attempts to celebrate diversity.

The reality is employees who identify as “different” in some way suffer greater burnout, feel a lesser sense of belonging, and experience more instances of microaggressions:

These employees find it much more difficult to be their true selves at work because they face discrimination and bias for simply being who they are.

Ironically, even well-intentioned D&I programs can damage workplace culture if employees believe the programs are ineffective. In such circumstances, employees are 4x more likely to think organizational D&I initiatives are not supported by leaders, twice as likely to think discrimination is a real problem at their organization, and 31% more likely to think their employer is more interested in labeling than accepting them.

For organizations to achieve an effective D&I strategy, they must completely rethink their efforts and redefine inclusion.

“When we listen and celebrate what is both common and different, we become a wiser, more inclusive, and better organization.”

—PAT WADORS, CHRO, SERVICENOW

INTERSECTIONALITY IS OFTEN IGNORED

Many organizations have a blind spot for intersectionality (a combination of two or more identities—race, gender, ability, sexual orientation, etc.—in the same person).5

This can create multiple disadvantages for intersectional individuals because they may experience discrimination based on any or all of their identities. For example, a Black LGBT woman might encounter microaggressions for her race, sexual orientation, and gender. Intersectionality multiplies potential discrimination and the impact of it.

A comparison of transgender and cisgender employees (those whose gender matches their assigned sex at birth) highlights the difference intersectionality makes. According to the data, a person who is transgender, regardless of whether they’re male or female, experiences more microaggressions due to this additional identity.

Ultimately, there are many employees whose multi-dimensional identities defy single, traditional categories. And unfortunately, the intersectionality of people means there is the potential for layers of bias and discrimination against them. This inequality in experience affects more than just the individual employee—it negatively impacts their peers and the culture as well.

“There is no such thing as single-issue struggle, because we do not live single-issue lives.”

—AUDRE LORDE, BLACK AUTHOR AND CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST

TO INCREASE INCLUSION, THINK SMALL

There are several existing models for addressing diversity, inclusion, and equality, but most of them miss a few important elements.

Some models take a top-down view showcasing strategies or initiatives the organization can implement to increase D&I in the workplace. They focus on compliance and social responsibility, or on efforts that touch employees at key milestones in the employee lifecycle, such as improving diversity in hiring and practicing inclusion in promotions and performance reviews. However, these models may lack senior-leader endorsement, meaningful prioritization, and funding. Additionally, they often overlook the small—and nearly infinite—everyday employee experiences.

Last year’s report demonstrated how the employee experience is comprised of frequent, common micro-experiences like the conversations people have with their teams, the environments in which they work, the messages they get from their company, and the feedback they receive from their leaders. It’s these little experiences that cumulatively determine how employees perceive their organization. And to address them, it helps to get curious. How can we make the employee experience itself more inclusive, not just when an employee gets hired and promoted, but when they go to lunch or meet with their leader? How often are they invited to work on special projects? How do they feel about the tools and resources they have? Do they receive appropriate recognition for their work?

Because these micro-experiences are often where discrimination and microaggressions occur, they clearly belong within the scope of D&I.

{{report_insert_1}}

EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION ARE NOT OPPOSITES

On the surface, it may appear that inclusion and exclusion are two sides of the same coin. The prevailing assumption around these terms is that when one goes up, the other goes down, and vice versa. Our research demonstrates that while exclusion and inclusion are related and do impact each other, they are not opposing measurements along the same continuum. They are separate groups of behaviors and should be considered, measured, and managed as such.

As part of this year’s research, we designed and tested two indices to measure inclusion and exclusion independently. What we’ve found is a more nuanced and complete picture of the employee experience. We see that as much as they are separate, inclusion and exclusion interact in a powerful way to influence culture, and we cannot improve inclusion without addressing exclusion.

Many forms of exclusionary behavior exist in the workplace. The data show five types have the most impact:

- Experiencing personal exclusion from special projects

- Experiencing personal exclusion from promotional opportunities

- Witnessing exclusion of another from promotional opportunities

- Witnessing instances of intentional discrimination

- Witnessing instances of unintentional discrimination

Is exclusion prevalent? Yes. Only 15% of employees report never having witnessed or personally experienced exclusionary behaviors. And the probability that a minority employee experiences or witnesses exclusion at their organization is 64% higher than for a non-minority employee.

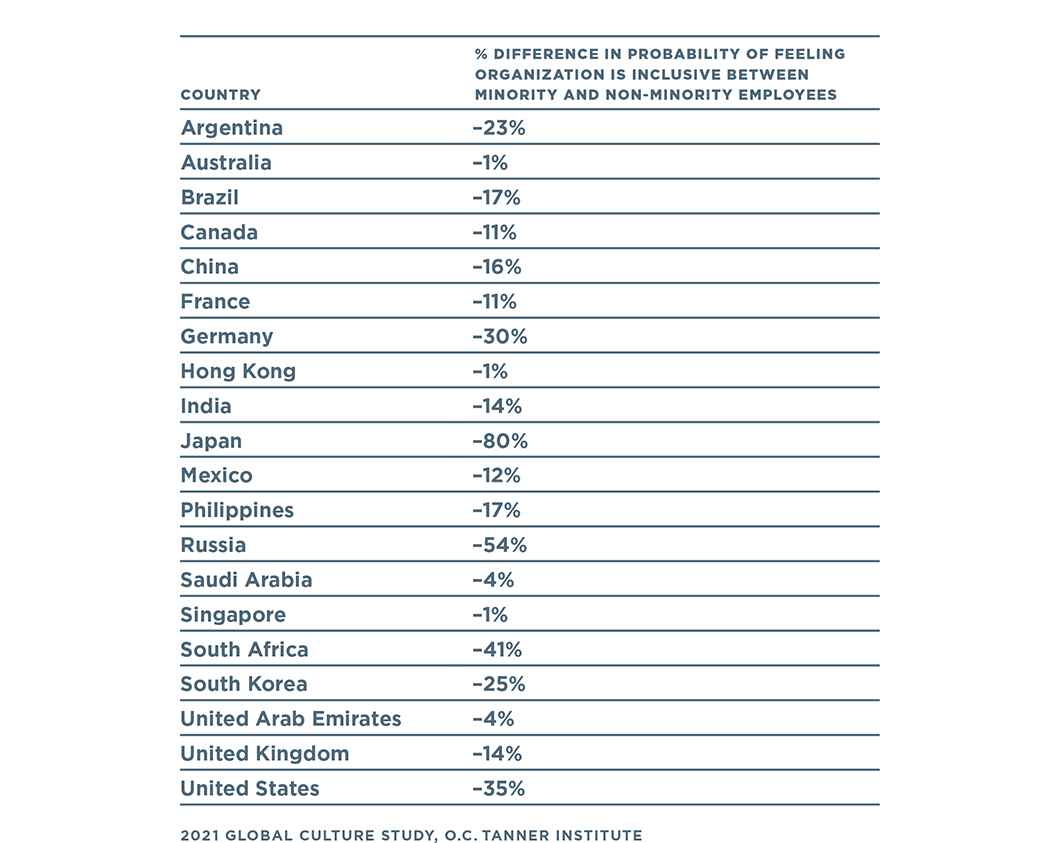

With deep racial tensions and protests across the US during the summer of 2020, many may wonder if exclusion is a larger problem in America due to the country’s history and broad demographic mix. Do other countries suffer from the same issues to the same degree? Our data show that exclusion is a big problem for employees and organizations across the globe, and the issues go well beyond race. Employees can feel excluded or marginalized based on gender, ethnic group within a race, class, sexual orientation, and other differences, which occur frequently in many countries. The table gives a good sense of the spectrum:

“The point isn’t to get people to accept that they have biases, but to get them to see that those biases have negative consequences for others.”

—THERESA MCHENRY, HR DIRECTOR, MICROSOFT UK

Inclusion, on the other hand, should be measured separately from exclusion because the perception of inclusion has a different effect on employee experience, culture, and business outcomes than exclusion. Also, different experiences create an employee’s perception of inclusion. We found five perceptions of inclusion (in no particular ranking):

- Every employee has access to the same opportunities

- Employees feel comfortable talking about D&I with leaders

- Leaders appreciate all aspects of individual employees

- Organization understands rather than categorizes employees

- Leadership represents employee opinions

The probability that an employee in any minority feels their organization is inclusive is 34% lower than it is for a non-minority employee. In the US, race and ethnicity play a significant role. Black employees are 9% less likely to feel their organization is inclusive than their white coworkers, while Asian, Hispanic, and Latino employees are 30% less likely to feel their organization is inclusive.

Similar to exclusion, inclusion is a challenge in many countries where minorities feel their organization’s culture is less inclusive than non-minorities do. In Argentina, Germany, Japan, Russia, South Africa, and South Korea, there is a considerable difference in the perception of inclusion between minority and non-minority employees.

“We want a culture that is inclusive of everyone and where everyone who joins feels they have opportunities to succeed and grow.”

—NELLIE BORRERO, MANAGING DIRECTOR, GLOBAL INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY, ACCENTURE

As mentioned previously, inclusion and exclusion play separate roles in employee perceptions of how inclusive their culture is. Both low exclusion and high inclusion can positively impact perceptions. But reducing exclusion without increasing inclusion can only do so much. When organizations simultaneously foster inclusion and minimize exclusion, we see much greater results:

Figure 6. THE BIFURCATION OF EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION

Inclusive and exclusionary behaviors are related but impact culture independently of each other.

The lesson here is organizations that only address acts of exclusion or only focus on making their cultures more inclusive will fail to maximize their results. Real, lasting progress requires effort on both fronts. When everyone in the organization—from senior leaders to interns—works daily to help employees feel included and empowered, and, at the same time, minimizes the negative experiences among minorities and employees who feel different, D&I efforts will be successful.

“Diversity, or the state of being different, isn’t the same as inclusion. One is a description of what is, while the other describes a style of interaction essential to effective teams and organizations.”

—BILL CRAWFORD, PSYCHOLOGIST AND AUTHOR

{{report_insert_2}}

RECOMMENDATIONS & IMPACT

Organizations should take the following steps to increase inclusion and enhance their cultures:

1. Build inclusion into multiple aspects of the employee experience

Effective diversity and inclusion efforts require everyone to understand and act—not just HR, a single department, only senior leaders, or other specified employees.

To make a culture inclusive, inclusion must be built into many parts of the employee experience. D&I efforts must be ongoing and consistent, not just one-off events, which may explain why half of employees feel inclusion initiatives are not a continuous priority.

Inclusion efforts should also focus on the everyday employee experience. A few specific suggestions:

Identify ways to help employees feel included. Start by examining team interactions, messages from senior leaders, conversations with direct managers, and the work environment. Organizations will know they’ve hit the mark when employees say the organization recognizes, appreciates, evaluates, and supports them equally.

Ensure employees have a voice, are given opportunities, and can accomplish great work without feeling excluded or being treated differently because of who they are. Make certain bias and exclusion are understood and called out. What employees see, hear, and experience from the organization should reinforce that it cares about inclusion.

Create programs with purpose and ensure they are embraced. Develop a plan with measurable goals and provide resources, tools, and training to help all employees be more inclusive. Hold leaders accountable, and have senior leaders talk about inclusion in their divisional and departmental meetings. Check in with employees to see how things are changing. When inclusion is treated as an intentional priority, it will become part of the culture.

Communicate consistently and frequently to leaders and employees to ensure inclusion stays top of mind. Our research shows just over half of employees say their senior leaders have communicated their D&I goals, 10% of employees do not recall seeing any communication about D&I, and over one-third say a month or more goes by between D&I communications.

“D&I needs to be something that every single employee at the company has a stake in.”

—BO YOUNG LEE, CHIEF DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION OFFICER, UBER

2. Teach leaders how to lead more effectively through inclusion

An essential part of revitalizing a D&I strategy is to develop leaders who have modern leadership skills. Leaders who mentor rather than direct, connect instead of gatekeep, and nurture a sense of purpose tend to foster more inclusive environments. Modern leaders are also more emotionally intelligent and able to navigate the complex, intersectional identities of their employees. By contrast, leaders who fail to cultivate inclusive environments tend to take a one-dimensional approach to D&I. They are often unaware of their biases and avoid complex conversations around diversity, inclusion, and intersectionality.

Modern leaders increase the probability an employee will feel their organization is inclusive by 9x. Employees of modern leaders also feel more included, engaged, and have improved employee experiences and culture scores. But cultivating modern leadership requires work at both the individual and organizational level. A couple suggestions:

Educate leaders on the fundamentals of intersectionality, enabling them to embrace their own unique identities and increase their awareness of various identities in others. Modern leaders are more likely to share personal experiences about their own intersectional identities (which leads to employees being 31% more likely to have an aspirational employee experience) and ask their employees about their experiences as well (which leads to employees being 2x more likely to feel their organization is inclusive).

Help leaders effectively communicate to employees that their unique identities are appreciated and valued. Employees who feel that appreciation are twice as likely to have a sense of belonging and twice as likely to have a high sense of all six Talent Magnets (purpose, opportunity, success, appreciation, wellbeing, and leadership). Odds of engagement and promoting the organization (eNPS) also double.

Encourage leaders to talk to employees in person about D&I efforts rather than rely on email. When leaders use meetings, employees are 197% more likely to feel an increased sense of belonging. When they use one-to-ones, that sense of belonging increases to 225%.

3. Invest in technology to assist D&I efforts

Forward-thinking organizations are employing new technology to help create diverse and inclusive cultures. AI, machine learning, natural language processing, and sentiment analysis can already help with recruiting, career development, training, and engagement. We also find the odds an employee agrees that their organization is inclusive increases when it has implemented technology in various areas of the employee experience:

Encourage leaders to talk to employees in person about D&I efforts rather than rely on email. When leaders use meetings, employees are 197% more likely to feel an increased sense of belonging. When they use one-to-ones, that sense of belonging increases to 225%.

Organizations that implement at least one element of D&I technology experience extremely positive cultural and business outcomes, including 152% greater odds of increasing revenue:

As with all inclusion initiatives, ongoing communication is key to ensuring D&I technology succeeds. When employees receive regular updates on how the technology is enhancing inclusion, they are:

{{report_insert_3}}

CONCLUSION

When talking about inclusion efforts in the workplace, leadership needs to change the conversation. It’s no longer about how to mold a diverse set of employees into an existing culture; it’s about how to create a culture that embraces who every individual is. Inclusion celebrates the intersection of different backgrounds, genders, races, abilities, sexual orientations, and other attributes. It allows organizations to discover new possibilities that only emerge when the perspectives, skills, and talents of many unique people are represented, respected, and integrated. And, of course, it’s ultimately as good for business as it is for employees.

If we evolve how we think of inclusion and ensure employees feel it in both peak and micro-experiences, the elusive dream of an inclusive organization becomes achievable.

“Diversity is the mix. Inclusion is making the mix work.”

—ANDRES TAPIA, SENIOR CLIENT PARTNER, KORN FERRY

INCLUSION—4 KEY TAKEAWAYS

Inclusion is seeing and valuing individuals for their unique selves, rather than labeling or categorizing based on demographics.

Exclusion and inclusion are not opposing dimensions on the same axis. They play separate roles in how inclusive an organization’s culture will be.

Inclusion efforts are most effective when focused on the employee’s everyday experience.

Frequent, consistent communication and education about inclusion efforts are critical to the success of D&I initiatives.

Inclusion Sources

1. “Inclusion,” Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed., 2003.

2. “What employees think about inclusion in the workplace,” Kristin Ryba, Quantum Workplace, October 10, 2019.

3, 6, 8, 9. “6 steps for building an inclusive workplace,” Kathy Gurchiek, SHRM, March 19, 2018.

4. “5 strategies for creating an inclusive workplace,” Pooja Jain-Link, Julia Taylor Kennedy, and Trudy Bourgeois, Harvard Business Review, January 13, 2020.

5. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” Kimberlé Crenshaw, University of Chicago Legal Forum 139-67, 1989.

7, 10. “How can you use technology to support a culture of inclusion and diversity?” David Green, myHRfuture, July 25, 2019.

CASE STUDY—INCORPORATING INCLUSION INTO EVERY EXPERIENCE

AutoDesk understands that their most impactful inclusion efforts are not formal programs or initiatives, but rather encompass the everyday interactions employees have with the company. Danny Guillory, Head of Global Diversity and Inclusion, recommends companies “determine the moments of truth in the workplace where any individual can impact diversity and inclusion. What is most impactful is not what the CEO says, not what I say, but the experiences I have with the five or six people I work with every day. What are the key moments almost every employee touches where they can have an impact?”

Autodesk encourages leaders to foster an environment where employees feel included in every meeting. Ideas such as distributing materials to review ahead of time, so an employee whose first language isn’t English, or who’s more introverted and not comfortable speaking up, can be prepared; rotating meeting times for employees in different time zones or with non-typical work schedules; being conscious of communication styles to avoid biased language like “mansplaining;” giving credit accurately; and calling out those who interrupt to ensure everyone has a chance to be heard.6

CASE STUDIES—TRAINING LEADERS ON INCLUSION

Organizations often assume leaders know how to build an inclusive culture. The truth is many don’t, and few know how to do it well. Some examples of companies educating leaders on the realities of inclusion:

Bankwest wanted a training method to demonstrate inclusive leadership in action. The answer was a virtual reality training series that allowed leaders to truly feel different interactions and learn from coworkers’ perspectives. 100% of participants agreed that the training was engaging and helped them internalize situations their colleagues face daily.7

American Express recently rolled out mandatory inclusion training for all leaders at the VP level and above. Training begins with what inclusion is and why it’s important. Then, in small groups, they discuss specific strategies for fostering inclusion.8

Merck & Co. requires every leader to have unconscious bias training and teaches them how to handle real-life issues like childcare and disability accommodations, as well as how to structure meetings, allocate resources, and use language that advances inclusion. Leaders then account for it in their performance reviews.9

CASE STUDY—TECHNOLOGY REFINES RECRUITING

Zillow, the online real estate and rental marketplace, decided to expand their recruiting pool by making the company’s communication feel more inclusive. When reaching out to “passive” candidates (people they are interested in speaking with but who have not yet applied), Zillow knew the wrong message—even a subtle one—could ruin their chances. So they used software to help them create outreach emails and recruitment materials with gender neutral language. This seemingly small change has increased the number of applicants who identify as women by 12%.10